At StackOne, we build integrations. Now obviously, AI agents are a huge oppurtunity for us, because for agents to be useful, they need to connect to the real world - CRMs, email, calendars etc. To understand the landscape and inform development, we need to know: what integrations are developers actually building with AI agents and how are they building them? What integrations matter most? What problems are they solving?

Unto this end, I built an agentic researcher that continuously monitors the web for AI agent use cases, and more importantly: gets better over time based on the team’s feedback.

The AI agent ecosystem is … expansive. LangChain, LangGraph, CrewAI, OpenAI Agents SDK, Claude tools - new frameworks appear weekly. Developers are building agents that connect to Salesforce, Gmail, Slack, HubSpot, and countless other services. But this information is scattered across Reddit posts, GitHub discussions, blog articles, and Twitter threads. As anyone in AI is well aware, the signal-to-noise ratio is horrifically, sickeningly overwhelming. Information is blasted everywhere, it’s altogether rather chaotic and not in a good way.

The first step was to build a simple pipeline that could monitor the web for relevant content, extract the information I needed and notify the team. The architecture looked like this:

Parallel Monitor API → Webhook Handler → Claude Extraction → Slack

Parallel continuously monitors the web for specific queries and sends webhooks when it finds relevant content. It’s pretty cool. They have a search api that I’ve used a lot as an MCP server but for this project I’m using the Monitor API, which is designed for continuous web monitoring with webhook delivery.

I setup a few monitors with broad queries like:

When Parallel finds a new matching page, it sends a webhook to the FastAPI handler hosted on Modal. Modal makes it super easy to deploy serverless applications with persistent storage and background tasks. This is perfect for handling webhooks. After we receive the webhook, we need to extract structured information from the messy web content. Naturally, we turn to more AI for this - who would’ve thought. After this, we send a Slack notification to a channel with the extracted use case details. Job done.

… and yet, obviously this wasn’t all there was to it.

The simple pipeline worked. Hooray. However, I quickly realised that the queries I had set up were … not good. We still had too much noise and not enough sauce - the monitors were returning a lot of irrelevant content. There was no way of evaluating the system because I didn’t have a system for evaluations because there was no measure of goodness of the new use-cases that we found.

We needed a feedback loop - it needed to get better over time and I didn’t want to be the bottleneck. Expertly tuning queries is tedious, error-prone and boring - so in summary, not really the best use of my time. What was the minimum viable way to get feedback from the team on what was good vs bad? We needed some measure of goodness for the use-cases that were being send as messages to Slack channels … 🤔🤔🤔 … some way of quickly reacting to messages 👀 … that could be easily done by humans and processed by a computer

…

💡

…

🔥👍👎

You guessed it - emojis, the modern heiroglyphic. This was ideal. We needed low-friction feedback from the team and we were already using Slack to send notifications and it’s really low effort to add reactions to messages. So I decided to use Slack reactions as feedback signals. 🔥 = 5 points, 👍 = 1 point, 👎 = -1 point.

Technically, this works by subscribing to the Slack Events API. When someone adds a reaction to a message, Slack sends a reaction_added event to my webhook handler. The handler extracts the message timestamp, fetches the original message to find the source URL, matches it to the use case in SQLite, and stores the reaction with its priority. The same flow handles reaction_removed events - if someone changes their mind, the feedback updates accordingly.

So now we are collecting feedback on the use cases the monitors find. But how do we close the loop and make the monitors better based on this feedback? Enter DSPy - prompt optimisation.

DSPy is a framework for building LLM-powered systems with built-in optimization loops (It makes it easy to optimise prompts). We can use DSPy to optimise the monitor queries based on the Slack reactions we collect. One important note: It’s diffucult to optimise the parallel monitor prompt with the monitor in the loop because the monitor API is an async system with wehbooks, so we can’t send a different version of the query back in time to see what it would’ve picked up. Instead, we have to use a proxy for the monitor to evaluate different queries. We do this by using embedding similarity to rank found use-cases against the query.

The optimization loop looks like this:

┌───────────┐

│ │

│ v

│ ┌───────────────────┐

│ │ DSPy Optimizer │

│ │ generates query │

│ └─────────┬─────────┘

│ │

│ v

│ ┌───────────────────┐

│ │ embedding_sim(... │

│ │ query, use_case) │

│ └─────────┬─────────┘

│ │

│ v

│ ┌───────────────────┐

│ │ reward(... │

│ │ ranking, reaction)│

│ └─────────┬─────────┘

│ │

└───────────┘

reward = Σ 5(🔥 top 10)

+ (👍 top 20)

- (👎 top 20)

The similarity function embeds both the use-case and the query using sentence transformers and computes cosine similarity. This gives us a ranking of how similar the use-cases to a given query. We can then combine this ranking with the reactions to compute a reward for the query, i.e. how well similar is the query to the positively reacted use-cases. This reward function allows us to use DSPy’s query optimization capabilities to improve the monitor queries, by generating different queries and finding ones that are more similar to the good use-cases. Obviously, this isn’t perfect - the similarity function is just a proxy for the actual monitor performance, but it’s good enough to start the optimisation engine. To really get this going, we would need a better proxy for the parallel monitor - maybe parallel might release a RAG-like search API for your own local database in the future, who knows.

The last thing to do was setup a weekly job to run the optimization loop and update the monitor queries. Now, every monday morning, the system reviews the previous week’s reactions, optimizes the queries, and updates the monitors accordingly. This way, the system continuously learns from the team’s feedback and improves over time.

After a week of running the system, I realised that having many granular monitors was causing sparse feedback signals. Each monitor was only getting a few reactions, making it hard for the optimizer to learn effectively. To address this, I decided to consolidate the monitors into two broader categories.

This consolidation meant that each monitor would capture a wider range of use-cases, increasing the likelihood of receiving reactions. With more data per query, the DSPy optimizer had a richer dataset to learn from, leading to better query improvements over time.

I also added some slack commands to manually trigger re-optimization and view current monitor queries. This gave the team more control and visibility into the system’s learning process.

Then, I also added a Google Sheets sync to allow for easier analysis of the use-cases found. The sheet automatically filters out use-cases with net negative reactions, keeping it clean and focused on the good stuff.

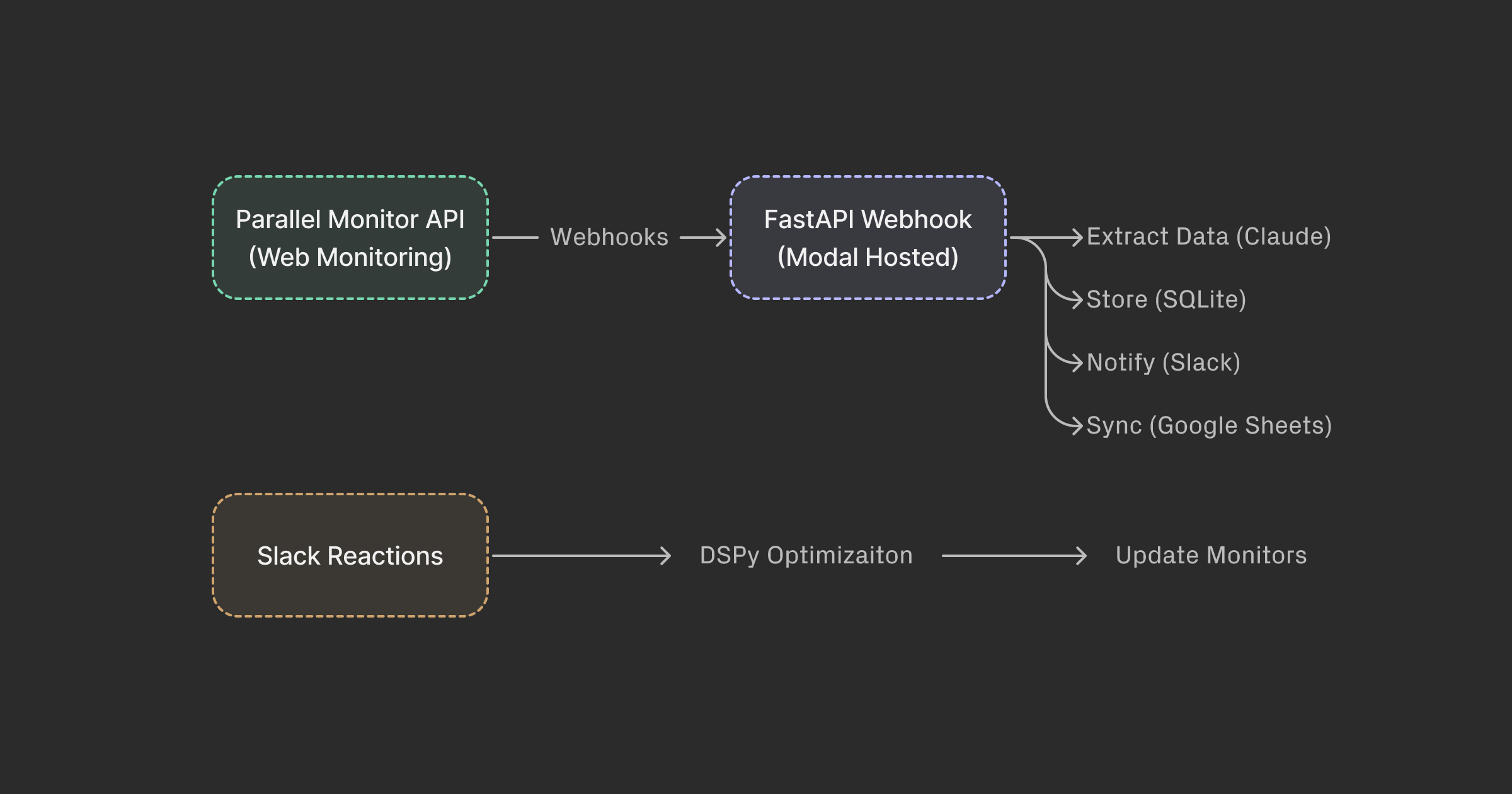

Here’s what we ended up with:

┌─────────────────────┐

│ Parallel Monitor API│

│ (Web Monitoring) │

└─────────────────────┘

│ Webhooks

v

┌─────────────────────┐

│ FastAPI Webhook │

│ (Modal Hosted) │

└─────────────────────┘

│

├─► Extract data (Claude)

│

├─► Store (SQLite)

│

├─► Notify (Slack)

│

└─► Sync (Google Sheets)

┌─────────────────────┐

│ Slack Reactions │──► DSPy Optimization ──► Update Monitors

└─────────────────────┘

What did I learn? It’s really easy to build agentic systems. The hardest part in building AI is usually the data collection and evaluation - in this system I’ve made this as easy as possible by leveraging Slack reactions as feedback signals. To actually encourage reactions, incentivising this with the lure of improving the system does wonders. The rest is was just engineering.